![[FileSize] => 22667 [FileType] => 2 [MimeType] => image/jpeg [SectionsFound] =>](https://phd.emilezile.com/media/pages/4500-lumens/d0f1532aeb-1655274411/untitled-1-q70.jpg)

![[FileSize] => 96956 [FileType] => 2 [MimeType] => image/jpeg [SectionsFound] =>](https://phd.emilezile.com/media/pages/4500-lumens/ac57e067c5-1655274412/dsc05749-q70.jpg)

![[FileSize] => 51185 [FileType] => 2 [MimeType] => image/jpeg [SectionsFound] =>](https://phd.emilezile.com/media/pages/4500-lumens/f77369219c-1655274411/j0002480-q70.jpg)

![[FileSize] => 94504 [FileType] => 2 [MimeType] => image/jpeg [SectionsFound] =>](https://phd.emilezile.com/media/pages/4500-lumens/626ff51098-1655274411/dsc05934-q70.jpg)

![[FileSize] => 54412 [FileType] => 2 [MimeType] => image/jpeg [SectionsFound] =>](https://phd.emilezile.com/media/pages/4500-lumens/5dbacc10a7-1655274411/j0002488-q70.jpg)

![[FileSize] => 119458 [FileType] => 2 [MimeType] => image/jpeg [SectionsFound] =>](https://phd.emilezile.com/media/pages/4500-lumens/914afaf2ac-1655274411/j0002629-q70.jpg)

4500 Lumens

CHAPTER EXCERPT

This work emerged from an invitation by NGV curators to engage with a space or gallery within the institution during the time of the Triennial, a large-scale exhibition of local and international contemporary art. An open invitation of such scope and freedom is daunting, and from my perspective it was important to avoid contemporary galleries, where I felt that the art historical references were too present, too contemporary, too unassailable. My wish to work within the 14th–16th Century Gallery stems from the sculptures being overlooked, sidelined, motionless and stuck in time. Uncool and uncontemporary, these sculptures exist beyond the purview of excited press releases and breathless gallery marketing. It is their unmoving austerity and sincerity that appeals to me when set in contrast to the larger structure of the Triennial. The darkness and minimal spotlight lighting in the gallery provide a backdrop for illumination, and the act of illumination is also a religious one.

The bright veneer of the NGV Triennial’s public image is a powerful force. NGV International is the fifth most Instagrammed place in Australia (NGV International n.d.) and is a prime example of institutional art gallery marketing logic that aims to create compelling and visually arresting art spaces for social media experiences, photographic consumption and sharing. The large scale of the Triennial forced my hand towards the darker (both physically and philosophically) zones of austere and sober early Christian sculpture. An example of this public-facing maximalism in the Triennial was the forecourt sculpture by Rafik Anadol. A towering monolithic screen of ever-changing amorphous and abstract imagery, said to be generated live by an algorithmic process behind the scenes, it was a live moving image that morphed and swayed. Monumental and demanding attention, the sculpture attracted audiences to be photographed with it and use it as an ever-changing backdrop for social media photography. Melbourne writer and artist Philip Brophy would describe the impact of the presence of the work to ‘grant virtual visceral thrills to hordes of Instagrammers without the negative publicity the NGV attracted in 1997 when it briefly exhibited Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ (1987)’ (Brophy 2021, N.p). The broad remit and curatorial framework of the Triennial exhibition towards a wide field of contemporary artwork pushed me to avoid such current artistic zones and seek a place which was in some sense beyond contemporary taste and criticism.

My interest in working with these sculptures stemmed from an appreciation for the medieval and Gothic periods, a period often referred to in Western history as the Dark Ages. The icons and artworks created in this time exist beyond the realm of contemporary rationality and technology. Existing in the historical context of being utilised as narrative devices to transfer moral allegories, these sculptures were placed in churches to aid in the expression of Christian storytelling to devout believers. I find in the sculptures a refreshing sombreness and stillness. The sculptures of saints and figures depict items attached to the particular saint’s narrative and mythos within the Christian allegorical structure, often depicting a wheel, a castle, a book, a crown or similar object, adjacent to the body of the saint depicted. The presence of these sculptures as austere physical figures allowed me to work with them in a performative manner to contrast and complement them.

///

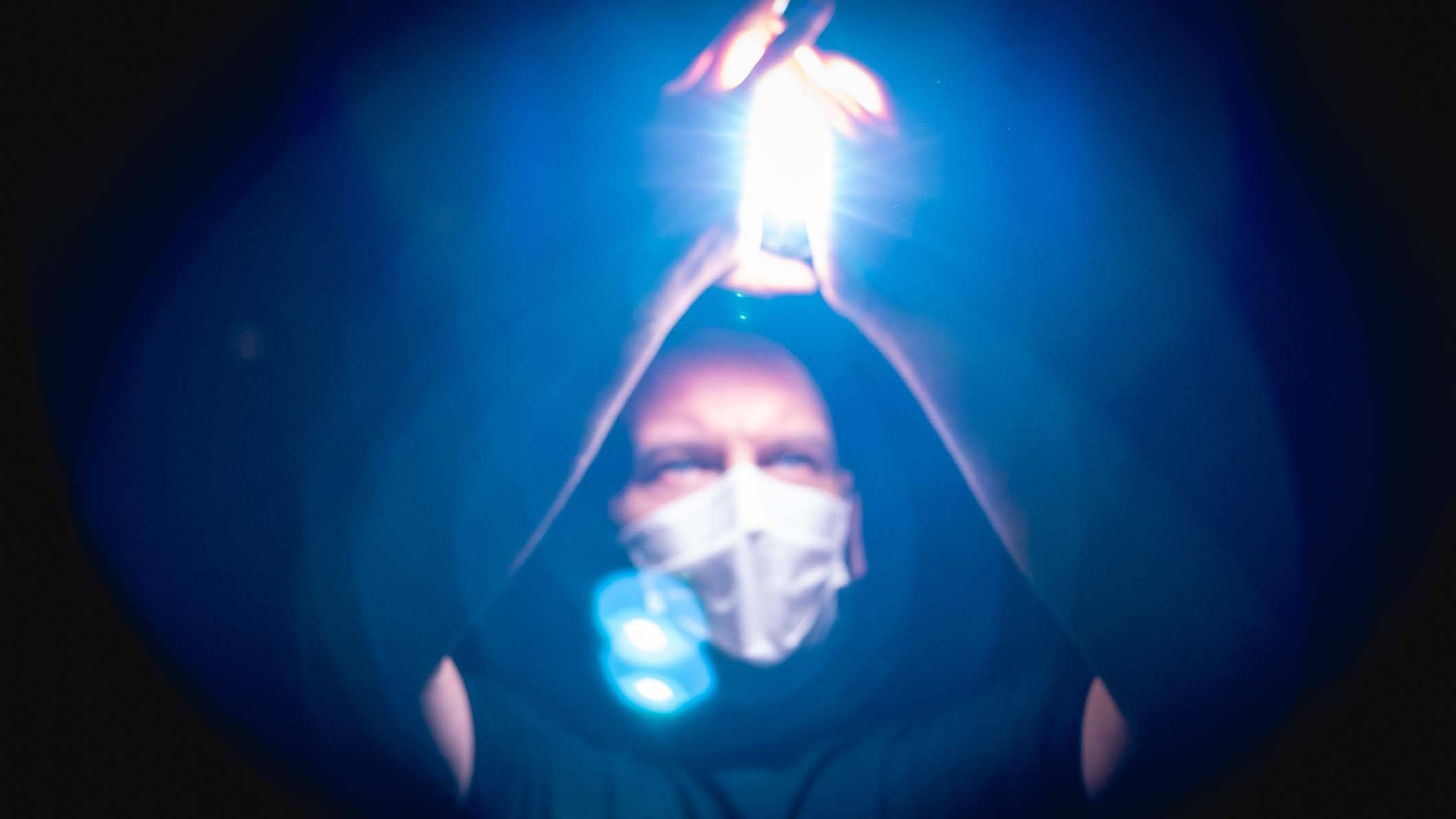

Using the six sculptures as the anchor of the performance, I move through the gallery with a high-powered handheld torch, performing hand gestures with the light creating a play with light and shadow on the sculptures. By modulating the light beam from the torch with my hand and gestures, I create expressive moments of dappled, expressive light to allow a new encounter between the sculptures, myself and the audience. My presence is foregrounded as I move around the room to create a series of performative personas in relation to the sculptures. Through the act of lighting and shadow-casting through gesture, I create new lighting conditions that bring forth features of the sculptures, at once not visible under traditional static museum lighting.

Through a manipulation and modulation of the light on and around these sculptures I am creating new moments in time to view the sculptures, physically engaging with sculpture from antiquity in a way which is not commonly accepted in a gallery; I am too close to the statues at times, I am bringing my physicality to bear on them, and use my physical presence in the room in a manner that is usually unwelcome in the controlled environment of an art gallery. The act of animating light around a subject gives the object a dimension of time; the moment light is cast upon them they are animated by a temporary layer of light upon their surfaces. An immobile sculpture temporarily wears a veil of light. In this rudimentary shadowplay, the aim is to reframe and re-present the sculptures and elicit additional character from them through my application of light. My application of light upon their surfaces using gestural movements becomes a dramaturgical device to direct the audience’s gaze. I describe this as applying a narrative meta-layer to the works, enabling them to be perceived within a performative structure that allows a beginning, middle and an end, under the applied gaze of the spotlight – a point I return to below.

The title of the work, 4500 Lumens, refers to the total output of light of the torch I am emitting, as measured in lumens. Early philosophers of antiquity developed a worldview that saw divine light as multi-modal, for example, Hellenistic Neoplatonist philosopher Plotinus would outline a worldview that saw divine light as both what emanates from a divine source to the individual, and that which emanates from the individual on to the world. Plotinus would describe these as complementary and entwined energea or energetic forces. The spotlight used in this performance is designed to be held in a pistol-grip mode and is built with rugged styling and protective rubber surrounding the LED unit to protect it from heavy knocks and drops. Typically, these LED spotlights are used in maritime, hunting and security applications, and are purchased from specialty electronics retailers, outdoor and camping shops. The number of lumens the lamp can emit is important as the bouncing effect of the beam is reduced with less luminosity.

///

A ‘mirroring act’ is defined by Cristina Albu as an encounter with one’s own self-image, ‘be it a reflection or a video projection, a series of dynamic interpersonal concatenations between affective experiences, behavioural responses, and imaginary projections’ (Albu 2016, 16). Albu refers to the works of Dan Graham and in her analysis of performers utilising mirrors to physicalise the sense of the self and other, self-presentation, performance and daily life. My work, 4500 Lumens, directly engages an audience with a collective mirroring act and aims to produce moments of personal yet intentionally limited agency for audience members. For example, in the final sequence of the performance, I distribute mirrors to audience members and allow them to participate in an act of reflecting a beam of light around the room and onto the sculptures. This sequence of the performance has a duration of four minutes and is linked to a passage of music. While I am present in the room and actively defining the use of the mirrors by giving and taking them from participants, I do not instruct them verbally on what to do or suggest through heavy-handed implication what they should be doing. Most participate in the distribution of the light beam around the room, some refuse. Once the music comes to its conclusion the performance is over and the moment of limited agency for the audience is complete. Aligning with Albu’s ‘mirroring act’ concept of a shared intersubjective moment using a mirror, these performances: offer the promise of a collectivity mediated by images or similar behavioural acts, yet deny access to a communal identity; they offer temporary intimacy in an unpredictable spatiotemporal interval, yet take away privacy, keeping spectators in a state of limbo between multiple unfulfilled possibilities (Albu 2016, 16).

By visualising a sense of connectedness and sociality, the communal mirroring act within 4500 Lumens emphasises the interconnectedness between disparate individuals yet displays how precarious and tenuous such relationships can be. By creating a moment of affective and temporary community among strangers, a tenuous infrastructure is established for the participants to establish codes of conduct without negotiation or speech, as they choose to bounce the light further or to collapse the link between the mirrors. A brief performative zone of social engagement is established. An implied social pressure exists to hold and bounce the beam of light successfully around the room.